You’ve probably heard the term “depth of field” before, but like many photographers, it may be a concept hard to visualize. I find the best way to understand things is by example, so here it goes.

Before we get to the example, let’s talk theory. Some of this I’ve already discussed, so please forgive the repetition. When the aperture (that’s the opening) of your lens is very wide, it lets in a lot of light. A wide aperture confusingly is given a small “f-stop” number, such as f1.4 or f2.8. When the aperture is very narrow, it lets in less light. This is given a larger f-stop number, such as f22 or f30. And there’s a whole slew of f-stop ranges in between ranging from wide open to almost completely closed.

A wider open aperture lets in more light, and therefore the shutter doesn’t need to be open as long as when you have a narrow aperture. This means to take the same exposure of the same photo, you will need to have a very slow shutter speed for a narrower aperture. Faster is better because you can hand hold the camera to take photos, and capture high speed action, right? Well that’s technically true, but there’s another factor in play here : depth of field.

A wider open aperture (e.g. f1.4) has a narrower depth of field. A narrow depth of field means things that you aren’t focusing on are blurry.

A narrower aperture (e.g. f22) has a much wider depth of field, meaning more of your composition will be in focus.

These facts are neither good nor bad – they just are.

Sometimes you want a wide depth of field, such as when you are doing landscape photography and you want the foreground and the background all in focus. Since you want a very narrow aperture, exposure time will be longer, so you’ll probably be using a tripod.

Why wouldn’t you always want as much as you can in focus, and use this wide depth of field? Many point and shoots try to give you as much depth of field as possible. In my opinion, this is not usually desirable.

When taking portraiture, a narrow depth of field helps isolate the subject, the person, from the background. If the background is tack sharp, that could distract from the subject that you are trying to focus on. Many beginner photographers try to get as much information in the scene, but this in the end makes for a boring scene. Simplicity and focus on the subject usually wins out. If you don’t believe me, take a look at the best photojournalism photos (e.g. http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/)

More expensive lenses are expensive because they are faster, which is another way of saying they have a wider aperture (or smaller f-stop number – this is confusing at first, I know).

One more thing – depth of field is not only controlled by the size of your aperture, but by your distance from the subject. The closer you are, the narrow the depth of field.

You can even use your eyes to prove this one out. Focus on something very close to you, and everything else (including things relatively close) is blurry. Focus on something farther away, and more objects are in focus.

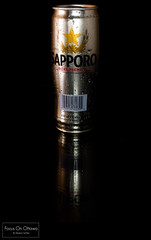

Okay – as promised, here are some examples to illustrate how the aperture controls the depth of field. I’m focusing on something fairly close to the lens, and note how the narrower the aperture, the more in focus the background building becomes. You can hopefully see how this can be used for creative control – neither the in focus nor the out of focus photos are better or worse than each other, they just produce a different outcome.

|

|